Ectopleura crocea

Geographic Range

Ectopleura crocea, also known as Ectopleura crocea in the scientific community, is commonly referred to as the pink-hearted hydroid, or the pink-mouthed clustered hydroid. It lives mainly in the northwest Atlantic ocean, including the area around New England, though it can be found from New Brunswick to Florida. In the Chesapeake Bay, Ectopleura crocea is limited to the mouth of the bay and is most prevalent in the summer(WDFW 2001; Lippson 1984; Collins 1981 )

- Biogeographic Regions

- atlantic ocean

Habitat

Ectopleura crocea grows profusely on rocks and boat docks. It does not, however, live in the intertidal zone, so it's not very likely that one would find Ectopleura crocea in this area though this invertebrate prefers a habitat consisting of gravel or sand (Animal Species in the Tillies Basin Area 2001).

Physical Description

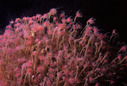

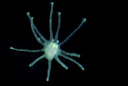

Hydroids are small (each about 400 micrometers in size), colonial animals that grow on rocks and seaweed and appear as "bushy growths." The hydroids appear as tufts of long and tangled stems. Individually, each hydroid has a stem-like feature, the pedicel, and a flower-like feature, the hydranth. Each hydranth has one row of tentacles around the central mouth and one proximal row, consisting of 16-25 shorter tentacles. Ectopleura crocea has gray stalks and pink hydranths, thus leading to its common names of "pink-hearted hydroid" or "pink-mouthed clustered hydroid," (Coelenterata 2001; Organisms of the Woods Hole Region 2001; Collins,Henry Jr. 1981).

- Other Physical Features

- ectothermic

- radial symmetry

Reproduction

In asexual reproduction, the gonosomes (long stalks) of Ectopleura crocea grow between the rows of tentacles into a cluster-like structure. Male and female gonophores are made by different colonies located on the gonosomes. Sperm is located within the structure of the balloon-resembling male gonophore. The eggs and developing larvae are contained within the female gonophore. Only a few oocytes reach maturity, in the cycle of sexual reproduction of Ectopleura crocea. The sperm then enters these oocytes and the egg ripens to a size of about 400 microns. Cleavage can form either a coeloblastula or a solid morula. The fertilized egg, now an embryo, is changed into an oval body of cells which will eventually flatten to take on a disc-like shape. The embryo then elongates into the shape of a cylinder. The height of the polyp attached to this body increases quickly and buds grow off the sides of the shoot (Colenterata 2001).

- Parental Investment

- no parental involvement

Behavior

Ectopleura crocea is a colonial invertebrate that groups itself together with other invertebrates of the same species in order to form dense colonies. It anchors itself onto rocks or boatdocks in order to maintain stability and avoid being washed away with the current. Ectopleura crocea are also very sensitive to increases in temperature (Coelenterata 2001).

Food Habits

The strength of the stinging power of Ectopleura crocea's tentacles paralyzes its prey and then the tentacles draw the food into the invertebrates' mouths. The food supply of Ectopleura crocea consists of zooplankton, phytoplankton and small detritus (CCS - Stellwagen Bank - Other Invertebrates (non-plankton));Animal Species in the Tilles Basin Area, 2001).

Economic Importance for Humans: Positive

Ectopleura crocea feeds on zooplankton, phytoplankton and small detritus, thus helping to avoid build-up in the environment. Also, it is a food source for nudibranchs, echinoderms, and other fish that humans regularly consume, including cod, haddock and flounder (Animal Species in the Tillies Basin Area 2001).

Economic Importance for Humans: Negative

Ectopleura crocea considered a nuisance species since it was introduced into the Atlantic environment approximately twenty years ago. (It was first found in the San Juan Islands in the 1930's but not discovered in the areas it inhabits now until the 1980's). Though most non-native species are unable to form self-sustaining colonies, if they do establish themselves, they can greatly affect the flora and the fauna of the ecosystem. Non-Indigenous Species (NIS) can bring disease and parasites to economically valuable native species and therefore adversely affect the economy. They also can compete for food with the native species or even use the native species as a food source, thus greatly altering the ecosystem (Mills 1998; Non-Indigenous Aquatic Nuisance Species (ANS),1998).

Conservation Status

Very little information was found on conservation of this species since it is not of threatened or endangered status. However, efforts are made to keep environmental conditions under control in order to maximize biodiversity.

-

- IUCN Red List

- No special status

-

- US Federal List

- No special status

-

- CITES

- No special status

Other Comments

In experimental studies, the larvae of Ectopleura crocea was observed to determine the importance of active and passive processes during its settlement. It was hypothesized that the larvae would have preferences of settlement based on topographic heterogeneity, that substratum complexity would modify these preferences and that behavior of the larvae on or close to the substratum mediates these preferences. All three hypotheses were found to be true. E. crocea larvae chose the most complex kind of panels and, for the most part, settled on surfaces that were the most exposed (Marine Ecology Progress Series 1996).

Contributors

Heather Seavolt (author), Western Maryland College, Louise a. Paquin (editor), Western Maryland College.

Glossary

- Atlantic Ocean

-

the body of water between Africa, Europe, the southern ocean (above 60 degrees south latitude), and the western hemisphere. It is the second largest ocean in the world after the Pacific Ocean.

- benthic

-

Referring to an animal that lives on or near the bottom of a body of water. Also an aquatic biome consisting of the ocean bottom below the pelagic and coastal zones. Bottom habitats in the very deepest oceans (below 9000 m) are sometimes referred to as the abyssal zone. see also oceanic vent.

- coastal

-

the nearshore aquatic habitats near a coast, or shoreline.

- ectothermic

-

animals which must use heat acquired from the environment and behavioral adaptations to regulate body temperature

- native range

-

the area in which the animal is naturally found, the region in which it is endemic.

- radial symmetry

-

a form of body symmetry in which the parts of an animal are arranged concentrically around a central oral/aboral axis and more than one imaginary plane through this axis results in halves that are mirror-images of each other. Examples are cnidarians (Phylum Cnidaria, jellyfish, anemones, and corals).

References

2001. "CCS - Stellwagen Bank - Other Invertebrates (non-plankton)" (On-line). Accessed May 7, 2001 at http://www.coastalstudies.org/stellwagen/invert.htm.

"Coelenterata" (On-line). Accessed April 21, 2001 at http://hermes.mbl.edu/BiologicalBulletin/EGGCOMP/pages/17.html.

1996. "Marine Ecology Progress Series" (On-line). Accessed May 7, 2001 at http://www.int-res.com/abstracts/meps/v135/pp77-87.html.

"Organisms of the Woods Hole Region" (On-line). Accessed April 30, 2001 at http://zeus.mbl.edu/public/organisms/index.php3?func=detail&id-2270.

1999. "Sustainable Seas Expeditions - Animla Species in the Tillies Basin Area" (On-line). Accessed May 7, 2001 at http://www.sanctuaries.nos.noaa.gov/special/teacherbook/sse_trb.pdf.

"WDFW - Non-Indigenous Aquatic Nuisance Species" (On-line). Accessed April 30, 2001 at http://www.wa.gov/wdfw/fish/nuisance/ans4.htm.

Collins, H. 1981. *Tubularia crocea*. Pp. 628 in Complete Field Guide to North American Wildlife. New York: Harper & Row.

Lippson, A., R. Lippson. 1984. Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Mills, C. 1998. "Commentary on species of Hydrozoa, Scyphozoa, and Anthozoa (Cnidaria)" (On-line). Accessed May 7, 2001 at http://faculty.washington.edu/cemills/PScnidaria.html.