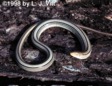

Ophisaurus attenuatusSlender Glass Lizard

Geographic Range

Slender glass lizards Ophisaurus attenuatus are native to the Nearctic region, specifically the eastern United States. There are two subspecies, western slender glass lizards Ophisaurus attenuatus longicaudus and eastern slender glass lizards Ophisaurus attenuatus attenuatus. Western glass lizards typically inhabit the western half of the range, and eastern glass lizards inhabit the eastern half of the range. This range is split by the Mississippi River Delta, an area that is absent of both subspecies. There is a disjunct group in Wisconsin, clustered around La Crosse and Reedsburg. Although they are endangered in Wisconsin, which subspecies this group contains is not recorded.

The northernmost point of western slender glass lizards' range is the southern side of Lake Michigan and their range continues southward to the southern tip of Texas. Western slender glass lizards are concentrated as far west as the middle of Kansas and continues eastwards to the Mississippi River Delta before continuing north through central Missouri and the south tip of Iowa stopping at Des Moines. Their range continues east through central Illinois. The eastern most point of their range is western Indiana. The western side of their range includes the east half of Texas just short of Abilene, the majority of Oklahoma except for the panhandle, the east half of Kansas, and ends after entering southern Nebraska, stopping just short of Johnson and Franklin County.

The western edge of eastern slender glass lizards' range begins on the eastern side of the Mississippi River Delta. It encompasses the very edge of western Louisiana, the majority of Mississippi (except the northwest corner), and the entirety of eastern Tennessee. Their range continues north though central Kentucky to Louisville. Their range travels eastward through the entirety of Alabama, Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina. Their range continues north through central North Carolina and into southeastern Virginia stopping just east of Charlottesville. (Hammerson, 2007; Holman, 1971; Mauger, 2015; McConkey, 1954)

Habitat

Slender glass lizards are terrestrial and inhabit temperate regions. Eastern slender glass lizards typically inhabit woodland edges, pine (Pinus) barrens, oak (Quercus) savannas, longleaf pine Pinus palustris flatwoods, and other dry forested places. Western slender glass lizards inhabit more early successional places such as prairies and grassland. Slender glass lizards tend to inhabit places with less canopy cover and plentiful woody debris. Nest locations include wooded areas located close to trails and clearings. Western slender glass lizards are also noted to reside beside small ponds and creeks. Blair (1961) observed western slender glass lizards positioned by a small pond and swimming considerable distances when disturbed on multiple occasions. Slender glass lizards are also fossorial, typically taking over and living in small mammals' burrows. Elevational limits have not been reported for these lizards. (Blair, 1961; Breitenbach, 2011; Fitch, 1989; Hammerson, 2007; Holman, 1971; McConkey, 1954)

- Habitat Regions

- temperate

- terrestrial

- Terrestrial Biomes

- savanna or grassland

- forest

- scrub forest

- Other Habitat Features

- riparian

Physical Description

Slender glass lizards are long serpentine lizards that are often mistaken for snakes because they have no legs. The two subspecies differ in markings and tail length. The tail of eastern slender glass lizards is nearly twice the size of the tails of western slender glass lizards. Slender glass lizards grow to a maximum total length of 1067 mm and a maximum snout-vent length (SVL) of 279 mm. Both subspecies possess a pronounced lateral fold that spans the length of their bodies. Male and female slender glass lizards do not differ in colors or patterns. Males slender glass lizards have longer SVL measures than females after 2 years.

Western slender glass lizards have an SVL of 220.5 mm and an average tail length of 351 mm. Their middorsal scales are dark in coloration and create a prominent stripe. The dorsal scales to the anterior and posterior of the middorsal stripe have a light brown or white pigmentation creating pale stripes perpendicular to the dark middorsal stripe. Three dark stripes are present directly anterior to the lateral fold and span the length of their body. These stripes break apart into dark spots at the anterior end of the lateral fold. The head of western slender glass lizards are the same light brown as the dorsal stripes. The light brown stripes present on the dorsum of older western glass lizards starts to deteriorate approximately halfway down their bodies. McConkey (1951) describes this as smudging. Older members of the species also start developing white spots in the darker areas of the anterior dorsum with the marks fading towards the posterior. Due to the white spots being surrounded by darker pigments this usually takes on the form of crossbars similar to eastern slender glass lizards. At around this time the light brown color of the head will darken into dark brown. Mass has not been recorded.

The most prominent difference between juvenile and mature western slender glass lizards is an absence of the dorsal stripe present in mature glass lizards. The dark lateral stripes are also more prominent than in mature glass lizards. Juvenile western slender glass lizards have an average SVL of 56.8 mm. Average tail length and mass have not been recorded.

Eastern slender glass lizards have an average SVL of 208 mm and their average tail length is 568 mm. Eastern slender glass lizards are much darker than the western subspecies with the dorsal scales being taken up by large crossbar patterns. The anterior two-thirds of the crossbars are dark brown with the posterior one-third section bearing white coloration. Therefore, each crossbar consists of a small white band bordered by large bands of dark brown. At the midline of the lizards the dorsal crossbars begin to distort with crossbar section alternating unpredictably and disappearing towards the posterior. Eastern slender glass lizards have a large dark colored middorsal stripe that spans the length of the glass lizard. However, unlike the vivid stripe of western glass lizards, eastern glass lizards' middorsal stripe blends due to their darker colored scales. They have stripes to the anterior and posterior of their lateral fold. These lateral stipes are evenly broken up with white spots, leading to a checkered pattern.

Juvenile eastern slender glass lizards also differ from mature members of the species. The most notable difference is the absence of dorsal crossbars and middorsal stripe typically seen in mature individuals. Eastern slender glass lizards have the lateral stripe pattern of mature individuals covering their entire body. They have an average snout vent length of 152 mm, but average tail length and average mass are not recorded. (Fitch, 1989; Holman, 1971; McConkey, 1954)

- Other Physical Features

- ectothermic

- bilateral symmetry

- Sexual Dimorphism

- male larger

-

- Range length

- 1067 (high) mm

- 42.01 (high) in

Development

Slender glass lizards hatch from early August to early October, with Fitch (1989) reporting an average hatch date of August 23rd in Kansas. Eggs are not temperature-sex-dependent. When hatched, they have an average snout-vent length (SVL) of 64 mm and an average total length of 196 mm. They initially grow at an average of 0.57 mm per day, with growth slowing to an average of 0.33 mm in autumn. Slender glass lizards exhibit indeterminate growth. For the first 2-years of development, male and female slender glass lizards develop at the same pace with an average SVL of 184 mm. Sexual maturity is reached at 2 years at which point males start growing faster than females. At the 3rd year of development males have an average SVL of 214 mm and females average 206 mm. At age 6, females have an average SVL of 232 mm, while males average 235 mm. At 9 years, male slender glass lizards may reach a maximum SVL of 259 mm. (Blair, 1961; Fitch, 1989; McConkey, 1954)

- Development - Life Cycle

- indeterminate growth

Reproduction

Slender glass lizards are polygynous, which means the males will mate with multiple females. With some contradiction, there is a significantly greater number of males present during the breeding season than females. Male slender glass lizards initiate the act of mating by nipping the females. If females are unresponsive, the males will bite the female's' skull or tail and attempt to insert their hemipenis into the females vent by making rhythmic swimming motions. If not reciprocal the females will flail and attempt to throw off the males. If unsuccessful, the males have been observed trying to mate with any nearby females via the same method. Fitch (1989) estimated that only 50% of slender glass lizard females mated each year. (Fitch, 1989)

- Mating System

- polygynous

Slender glass lizards breed seasonally and are iteroparous. They produce one clutch of eggs per breeding season (early April to early June), once a year. Males and females reach sexual maturity at their second year with a snout-vent length of 184 mm. Slender glass lizards reproduce through internal fertilization. Males will deposit sperm into the female's' vent through a hemipenis. Males’ testicular size will be at their largest from early April to the middle of May, and females will, in kind, have enlarged ovarian follicles. The gestation period before the eggs are laid has not been recorded. Clutch size can range from 5 to 16, and females stay with the clutch until hatching. The eggs average 21 mm by 16 mm. The eggs are reported to have an incubation time of 53 days. Slender glass lizards are born with an average snout-vent length of 57 mm and an average total length of 196 mm. Clutch mass (the weight of the clutch as a whole) averages 15 grams. Slender glass lizards hatch at weights between 5.13 g and 18.89 g, and average 15.03 g. Slender glass lizards are independent the moment they hatch. (Blair, 1961; Fitch, 1989; Trauth, 1984)

- Key Reproductive Features

- iteroparous

- seasonal breeding

- gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate)

- sexual

- fertilization

- oviparous

-

- Breeding interval

- Slender glass lizards produce one clutch a season.

-

- Breeding season

- April-June

-

- Range number of offspring

- 5 to 16

-

- Average time to independence

- 0 minutes

-

- Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female)

- 2 years

-

- Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male)

- 2 years

Female slender glass lizards stay with and protect the clutch before they hatch. They do this by curling around and covering the brood with their body, providing a barrier between the clutch and the environment. Although female glass lizards guard the clutch there is no actually evidence of direct benefit from this action, with the female glass lizards not increasing the temperature of the eggs or deterring predators. Males do not provide any parental investment beyond the act of mating. Female slender glass lizards are also known to use oophagy, which is the practice of eating unhealthy eggs to protect the healthy eggs from bacteria or other harmful stimuli. Young slender glass lizards are born precocial and are fully developed when they are born. Parental investment ends after the young hatch. (Blair, 1961; Fitch, 1989; Groves, 1982; Somma, 1990; Trauth, 1984)

- Parental Investment

- precocial

-

pre-hatching/birth

-

protecting

- female

-

protecting

Lifespan/Longevity

Fitch (1989) marked and followed 2116 slender glass lizards for 9 years. After 1-year, 1688/2116 (79.8% survivorship) slender glass lizards remained, with the population sharply dropping after that point. After two years, 261 (12.3% survivorship) glass lizards were left, and after three years the number dropped to 81 (3.8%). Years 4 (2.1%), 5 (1.2%), and 6 (0.5%) showed predictable survivorship declines. Year 6 was the last year a female was observed alive. The last living member of the generation was last measured to be alive at the 9th year. While there are no studies on lifespan in captivity for slender glass lizards, eastern glass lizards Ophisaurus ventralis are recorded to have a maximum lifespan of 14.8 years in captivity. It is likely that slender glass lizards have a similar lifespan if kept in captivity. (Fitch, 1989; Slavens and Slavens, 1999)

-

- Range lifespan

Status: wild - 9 (high) years

- Range lifespan

Behavior

Slender glass lizards are generally skittish and run away when threatened. They can detach their tails to evade predation, which explains their “glass” name. Fitch (2003) reported that almost 80% of adult specimens had lost and regenerated their tails. Even the release of the slender glass lizards into the wild prompted the detachment of their tails. Western slender glass lizards are natatorial, which means they can swim to get away from predators. They have been observed to swim 15-20 meters when threatened. Slender glass lizard movement is slow and erratic to hide from predators, with frequent stops. They typically don't range outside of a few square meters. Slender glass lizards are saltatorial which means they can jump to get away from predators.

They are also fossorial, and commonly make their nests in small burrows underground. They can commandeer tunnels of small mammals such as prairie voles Microtus ochrogaster and eastern moles Scalopus aquaticus if they need deeper tunnels for events like egg-laying and hibernation.

Slender glass lizards use behavioral thermoregulation, which means they base their activity on the temperature. If it is too hot they will become active at night and exhibit nocturnal tendencies, and they will become diurnal if it is too cold during evening hours. They hibernate in the winter when it gets too cold. The hibernation site is required to be below the frost line and to protect against small mammals.

Mating behavior is tactile and involves biting and thrashing. Male slender glass lizards initiate the act of mating by nipping the females. If not reciprocal the females will flail and attempt to throw off the males. (Blair, 1961; Breitenbach, 2011; Fitch, 1989; Fitch, 2003; McConkey, 1954; Wass and Gerald, 2017)

- Key Behaviors

- fossorial

- saltatorial

- natatorial

- diurnal

- nocturnal

- motile

- hibernation

Home Range

Slender glass lizards' home ranges do not have a focal point like a permanent burrow. These lizards can dig a small den underneath detritus or commandeer an existing tunnel dug by small mammals such as moles. Because of these practices it is not abnormal for slender glass lizards’ home ranges to continually shift.

Female slender glass lizards home ranges (0.20 ha) are typically half of male home ranges of 0.44 ha. The average home range for 1-year old juveniles is 0.16 hectares, 2-year juveniles is 0.14 hectares, 3-year glass lizards is 0.24 hectares, and 4-year glass lizards is 0.22 hectares.

Because slender glass lizards are constantly shifting their home ranges, they do not defend a set territory. (Fitch, 1989)

Communication and Perception

Slender glass lizards use odors to perceive and interact with the world. Slender glass lizards do this by using Jacobson's Organ which helps them use chemical clues and prey odors to hunt their meals. This is typically observed as a rapid movement of the tongue. This tongue movement is much higher than in other lizards who do not use this method to hunt prey. Fitch (1989) tested the response of 12 different lizards' hatchlings responses to prey odors applied to cotton swabs. Of the 12, slender glass lizards were the most responsive. Researchers hypothesized (based on field observations) that these lizards are active foragers. Fitch (1989) hypothesized that slender glass lizards used a sit-and-wait style of hunting instead of an active foraging approach.

Mating involved tactile senses like biting and thrashing, as well as visual chasing. Male slender glass lizards initiate the act of mating by nipping the females. If females are unresponsive, the males will bite the female's' skull or tail and attempt to insert their hemipenis into the females vent by making rhythmic swimming motions. If not reciprocal the females will flail and attempt to throw off the males. (Cooper Jr., 1990; Fitch, 1989; Forys and Allen, 2002; Groves, 1982; McConkey, 1954)

- Other Communication Modes

- pheromones

Food Habits

Slender glass lizards consume insects such as grasshoppers (order Orthoptera), cicadas (Order Hemiptera), crickets (order Coleoptera), ants (Order Hymenoptera), caterpillars (Order Lepidoptera), cockroaches (order Blattodea), and beetles (order Coleoptera). They eat non-insect arthropods like spiders (Order Araneae). They eat molluscs such as snails (family Gastropoda). Slender glass lizards consume other lizards and can be cannibalistic in captivity. They eat eggs out of their own nests if they are unhealthy. They will occasionally eat vertebrates such as small mice and ground-nesting birds. (Cooper Jr., 1990; Forys and Allen, 2002; Groves, 1982)

- Primary Diet

-

carnivore

- eats terrestrial vertebrates

- eats eggs

- insectivore

- eats non-insect arthropods

- molluscivore

- Animal Foods

- reptiles

- eggs

- insects

- terrestrial non-insect arthropods

- mollusks

Predation

Known predators of slender glass lizards are numerous. Mammalian mesopredators include: Virginia opossums (Didelphis virginiana), coyotes (Canis latrans), gray foxes (Urocyon cinereoargenteus), red foxes (Vulpes vulpes), bobcats (Lynx rufus), raccoons (Procyon lotor), striped skunks (Mephitis mephitis), and eastern spotted skunks (Spilogale putorius). Likely egg predators also include smaller mammals like eastern moles (Scalopus aquaticus), Elliot's short-tailed shrews (Blarina hylophaga), white-footed mice (Peromyscus leucopus), and western harvest mice (Reithrodontomys megalotis).

Avian predators include broad-winged hawks (Buteo platypterus) and red-tailed hawks (Buteo jamaicensis). Finally, serpentine predators are listed as copperheads (Agkistrodon contortrix), yellow-bellied racers (Coluber constrictor), prairie kingsnakes (Lampropeltis calligaster), and northern ring-necked snakes (Diadophis punctatus).

Slender glass lizards have evolved to escape and hide from predators. They are cryptic, which means their scales are patterned in a way that lets them camouflage themselves in their typical grassy habitats. Slender glass lizards are also fossorial, sleeping and hibernating in burrows to hide from predators. They are also natatorial and can swim up to 15-20 meters when threatened. They are saltatorial, which means they are capable of jumping to escape predators. Due to the fire dependent nature of their habitat, they can be vulnerable to predation after a fire due to the lack of cover and those have an increased rate of reproduction.

Althgouth these lizards are prey to dozens of different animals, no single animal uses them as a primary food source. Fitch (1989) observed that slender glass lizards probably comprised a very small part of these predators' diets. (Fitch, 1989; Fitch, 2003; Wass and Gerald, 2017)

-

- Known Predators

-

- Virginia opossums (Didelphis virginiana)

- coyotes (Canis latrans)

- gray foxes (Urocyon cinereoargenteus)

- red foxes (Vulpes vulpes)

- bobcats (Lynx rufus)

- raccoons (Procyon lotor)

- striped skunks (Mephitis mephitis)

- eastern spotted skunks (Spilogale putorius)

- eastern moles (Scalopus aquaticus)

- Elliot's short-tailed shrews (Blarina hylophaga)

- white-footed mice (Peromyscus leucopus)

- western harvest mice (Reithrodontomys megalotis)

- broad-winged hawks (Buteo platypterus)

- red-tailed hawks (Buteo jamaicensis)

- copperheads (Agkistrodon contortrix)

- northern ring-necked snakes (Diadophis punctatus)

- yellow-bellied racers (Coluber constrictor)

- prairie kingsnakes (Lampropeltis calligaster)

Ecosystem Roles

Slender glass lizards are primarily insectivores and eat a variety of arthropods including but not limited to ants, spiders, caterpillars, and cicadas. Slender glass lizards are a prey species for a mesopredator mammals, birds of prey, and snakes.

The only documented parasitic species of slender glass lizards is a common pest chigger called the harvest mite (Eutrombicula alfreddugesi). Slender glass lizards are highly resistant to this parasite as their scales limit chigger attachment. Slender glass lizards will commonly void tapeworms of an unspecified type but will suffer no ill effects associated with this parasite. It is theorized that one of the lizard's prey such as grasshoppers or crickets were the intermediate host, but no official study has been conducted. (Fitch, 1989; Holman, 1971; McConkey, 1954)

- Common chigger or harvest mite (Eutrombicula alfreddugesi)

Economic Importance for Humans: Positive

Slender glass lizards' diets consist primarily of insect species. Is it possible that they help control pest populations, but no studies support this jump. Slender glass lizards are occasionally kept as pet. Between 1990-1994, just 14 slender glass lizards were harvested in Florida for the pet trade. (Enge, 2005; Fitch, 1989; McConkey, 1954)

- Positive Impacts

- pet trade

Economic Importance for Humans: Negative

Slender glass lizards have no negative economic impact for humans. (Fitch, 1989; Holman, 1971; McConkey, 1954)

Conservation Status

Slender glass lizards are currently endangered in Wisconsin. The IUCN Red List records them as a species of "Least Concern." The U.S. federal list, CITES, and state of Michigan lists give no special status to slender glass lizards.

The main factor threatening the slender glass lizards are conversion of their habitats for human use. Primarily, their suitable grasslands are being converted to heavy-use agricultural lands that are no longer suitable for these lizards.

Despite being state-listed in Wisconsin (per the Wisconsin Wildlife Action Plan), there appear to be no conservation efforts enacted in the state or across their range. Slender glass lizards do inhabit many protected areas, like national and state parks, affording them some protection of suitable lands. ("2015-2025 Wisconsin Wildlife Action Plan", 2015; Breitenbach, 2011; Hammerson, 2007)

-

- IUCN Red List

-

Least Concern

More information

-

- IUCN Red List

-

Least Concern

More information

-

- US Federal List

- No special status

-

- CITES

- No special status

-

- State of Michigan List

- No special status

Contributors

Shad Hannabass (author), Radford University, Karen Powers (editor), Radford University, Victoria Raulerson (editor), Radford University, Christopher Wozniak (editor), Radford University, Genevieve Barnett (editor), Colorado State University.

Glossary

- Nearctic

-

living in the Nearctic biogeographic province, the northern part of the New World. This includes Greenland, the Canadian Arctic islands, and all of the North American as far south as the highlands of central Mexico.

- bilateral symmetry

-

having body symmetry such that the animal can be divided in one plane into two mirror-image halves. Animals with bilateral symmetry have dorsal and ventral sides, as well as anterior and posterior ends. Synapomorphy of the Bilateria.

- carnivore

-

an animal that mainly eats meat

- chemical

-

uses smells or other chemicals to communicate

- diurnal

-

- active during the day, 2. lasting for one day.

- ectothermic

-

animals which must use heat acquired from the environment and behavioral adaptations to regulate body temperature

- fertilization

-

union of egg and spermatozoan

- forest

-

forest biomes are dominated by trees, otherwise forest biomes can vary widely in amount of precipitation and seasonality.

- fossorial

-

Referring to a burrowing life-style or behavior, specialized for digging or burrowing.

- hibernation

-

the state that some animals enter during winter in which normal physiological processes are significantly reduced, thus lowering the animal's energy requirements. The act or condition of passing winter in a torpid or resting state, typically involving the abandonment of homoiothermy in mammals.

- indeterminate growth

-

Animals with indeterminate growth continue to grow throughout their lives.

- insectivore

-

An animal that eats mainly insects or spiders.

- iteroparous

-

offspring are produced in more than one group (litters, clutches, etc.) and across multiple seasons (or other periods hospitable to reproduction). Iteroparous animals must, by definition, survive over multiple seasons (or periodic condition changes).

- molluscivore

-

eats mollusks, members of Phylum Mollusca

- motile

-

having the capacity to move from one place to another.

- natatorial

-

specialized for swimming

- native range

-

the area in which the animal is naturally found, the region in which it is endemic.

- nocturnal

-

active during the night

- oviparous

-

reproduction in which eggs are released by the female; development of offspring occurs outside the mother's body.

- pet trade

-

the business of buying and selling animals for people to keep in their homes as pets.

- pheromones

-

chemicals released into air or water that are detected by and responded to by other animals of the same species

- polygynous

-

having more than one female as a mate at one time

- riparian

-

Referring to something living or located adjacent to a waterbody (usually, but not always, a river or stream).

- saltatorial

-

specialized for leaping or bounding locomotion; jumps or hops.

- scrub forest

-

scrub forests develop in areas that experience dry seasons.

- seasonal breeding

-

breeding is confined to a particular season

- sexual

-

reproduction that includes combining the genetic contribution of two individuals, a male and a female

- tactile

-

uses touch to communicate

- temperate

-

that region of the Earth between 23.5 degrees North and 60 degrees North (between the Tropic of Cancer and the Arctic Circle) and between 23.5 degrees South and 60 degrees South (between the Tropic of Capricorn and the Antarctic Circle).

- terrestrial

-

Living on the ground.

- tropical savanna and grassland

-

A terrestrial biome. Savannas are grasslands with scattered individual trees that do not form a closed canopy. Extensive savannas are found in parts of subtropical and tropical Africa and South America, and in Australia.

- savanna

-

A grassland with scattered trees or scattered clumps of trees, a type of community intermediate between grassland and forest. See also Tropical savanna and grassland biome.

- temperate grassland

-

A terrestrial biome found in temperate latitudes (>23.5° N or S latitude). Vegetation is made up mostly of grasses, the height and species diversity of which depend largely on the amount of moisture available. Fire and grazing are important in the long-term maintenance of grasslands.

- visual

-

uses sight to communicate

- young precocial

-

young are relatively well-developed when born

References

Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. 2015-2025 Wisconsin Wildlife Action Plan. Pub-NH-938. Madison, Wisconsin: Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. 2015.

Blair, A. 1961. Notes on Ophisaurus attenuatus attenuatus (Anguidae). The Southwestern Naturalist, 6/3-4: 201.

Breitenbach, L. 2011. Sampling Methods and Habitat Selection by the Western Slender Glass Lizard (Ophisaurus attenuatus) at Fort McCoy, Wisconsin (Master's Thesis). Stevens Point, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point.

Camposano, B., E. Smith. 2014. Ophisaurus attenuatus. Herpetological Review, 45/2: 283.

Cooper Jr., W. 1990. Prey odor discrimination by anguid lizards. Herpetologica, 46/2: 183-190.

Enge, K. 2005. Amphibians and Reptiles: Status and Conservation in Florida. Malabar, Florida: Krieger Publishing Company.

Fitch, H. 2003. A comparative study of loss and regeneration of lizard tails. Journal of Herpetology, 37/2: 395-399.

Fitch, H. 1989. A field study of the slender glass lizard, Ophisaurus attenuatus, in northern Kansas. University of Kansas Museum of Natural History Occasional Paper, 125: 1-50.

Forys, E., C. Allen. 2002. Functional group change within and across scales following invasions and extinctions in the Everglades ecosystem. Ecosystems, 5: 339-347.

Groves, J. 1982. Egg-eating behavior of brooding five-lined skinks, Eumeces fasciatus. Copeia, 1982/4: 969-971.

Hammerson, G. 2007. "Ophisaurus attenuatus" (On-line). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2007: e.T63716A12709295. Accessed September 07, 2021 at https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2007.RLTS.T63716A12709295.en.

Holman, A. 1971. Reptilia: Squamata: Sauria: Anguinidae Ophisaurus attenuatus. Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles, 111: 1-3.

Lee, J. 2009. The herpetofauna of the Camp Shelby joint forces training center in the Gulf Coastal Plain of Mississippi. Southeastern Naturalist, 8/4: 639-652.

Mauger, D. 2015. Current distribution and status of amphibians and reptiles in Will County, Illinois. Illinois Natural History Survey Bulletin, 40/1: 2-24.

McConkey, E. 1954. A systematic study of the North American lizards of the genus Ophisaurus. The American Midland Naturalist, 51/1: 133-171.

Mierzwa, K., S. Cortwright, D. Beamer. 1999. Amphibians and reptiles of the Grand Culmet River basin. Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science, 108/109: 105-121.

Pleyte, T. 1976. A study of a population of the slender glass lizard in Waushara Co., Wisconsin. Field Station Bulletin, 9/2: 16-19.

Shine, R. 2006. Relative clutch mass and body shape in lizards and snakes: Is reproductive investment constrained or optimized?. Evolution, 46/3: 828-833.

Slavens, F., K. Slavens. 1999. "Longevity-lizard index" (On-line). Frank and Kate's Web Page. Accessed November 09, 2021 at http://www.pondturtle.com/.

Somma, L. 1990. A Categorization and Bibliographic Survey of Parental Behavior in Lepidosaurian Reptiles. National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC: Smithsonian Herpetological Information Service.

Trauth, S. 1984. Seasonal incidence and reproduction in the western slender glass lizard, Ophisaurus attenuatus attenuatus (Reptilia, Anguidae), in Arkansas. The Southwestern Naturalist, 29/3: 271-275.

Vogt, R. 1981. Natural History of Amphibians and Reptiles in Wisconsin. Milwaukee, Wisconsin: Milwaukee Public Museum.

Wass, E., G. Gerald. 2017. Performance and kinematics of saltation in the limbless lizard Ophisaurus attenuatus (Squamata: Anguidae). Phyllomedusa, 16/1: 81-87.