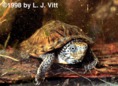

Sternotherus minorLoggerhead Musk Turtle

Geographic Range

Loggerheaded musk turtles (Sternotherus minor minor) and stripe-necked musk turtles (Sternotherus minor peltifer) are found in the southeastern region of the United States. Loggerhead musk turtles range from central Florida north to Virginia and as far west as Louisiana. Loggerhead musk turtles are more commonly found in the aquatic areas of the Tennessee River (Tennessee and Alabama), Ogeechee River (Georgia), and as far westward as the Pearl River (south-central Mississippi).

Stripe-necked musk turtles are more commonly found in the fast-flowing bodies of water like the aquatic areas of the Cumberland Plateau region. They range from the Pearl River of south-central Mississippi as far north as eastern Tennessee. (Buhlmann, et al., 2008; Ernst and Barbour, 1989; Iverson, 1977)

Habitat

Loggerhead musk turtles live in freshwater areas such as springs, ponds formed by sinkholes, rivers, swamps, and oxbow lakes. They are often found in places that are rich in vegetation. They are frequently found in high velocity habitats, but also occur in low velocity habitats. The substrate can be either rock or sand. They can hide underwater in crayfish burrows, under submerged logs, and rock crevices. They have been found at temperatures of 22 degrees Celsius and can stay submerged underwater for 60 hours in aerated water. A fully aquatic species, these turtles may stay submerged indefinitely in ideal conditions. They live in shallow water that ranges from 0.5-1.5m, but they have been found in water as deep as 13m. (Ernst and Barbour, 1989; Gatten, 1984; Mitchell, 1994; Niemiller, et al., 2013; Zappalorti and Iverson, 2006)

- Habitat Regions

- freshwater

- Aquatic Biomes

- lakes and ponds

- rivers and streams

-

- Range depth

- 0.5 to 13 m

- 1.64 to 42.65 ft

Physical Description

Loggerhead musk turtles range from around 7.5-11.5 cm in carapace length. The carapace length of males can reach up to 12 cm while a females can reach 14.5 cm. Their carapace color ranges from dark brown to orange, but they always have a darker border. The skin of the turtles can be brown or gray with spots. As juveniles, the patterns are bolder. The feet are webbed. Males tails are thicker and longer and older males have enlarged heads compared to adult females.

Stripe-necked musk turtles have yellow striped markings on their necks. While there hasn't been much research on the maturity of stripe-necked musk turtles, the largest found is 11.7cm.

In both subspecies, males are slightly shorter in carapace length (by about 4 mm) and have thicker tails. Males also have darker heads. (Ernst and Barbour, 1989; Mitchell, 1994; Niemiller, et al., 2013)

- Other Physical Features

- ectothermic

- bilateral symmetry

- Sexual Dimorphism

- female larger

- sexes shaped differently

Development

The eggs of loggerhead musk turtles are brittle, pink, and transparent when they are first laid, they then turn white once they start to develop. Incubation time averaged around 99 days. Eggs that are at a constant rate of 25 degrees Celsius take around 11 days to start developing and eggs that are chilled in an environment of 18-22 degrees Celsius take around 48 days. The eggs range from 12.7-19.5 mm in size and 1.97-6.70 g in mass. Once hatched the turtles plastral sizes ranged from 16.6-21.3 mm. It was recorded that juveniles have a plastral growth rate ranging from 0.31-1.45 mm per month. Females mature around 4.5-8 years and males mature around 3-6 years. Loggerhead musk turtles and stripe-necked musk turtles are both temperature sex determinant. Males develop at temperatures of 25-26 C, while females are more common below 24 C and above 27 C. (Ernst and Barbour, 1989; Iverson, 1978; Niemiller, et al., 2013; Zappalorti and Iverson, 2006)

- Development - Life Cycle

- temperature sex determination

Reproduction

Female loggerhead musk turtles have an ovarian cycle that is continuous but slows down in the summer months. Ovulation occurs from October to July and male testicular cycles peak 5 months before female ovulation begins. Mating peaks in the morning of the months of April and May. All mating happens when the turtles are submerged. They are polygynandrous. Males chase females and once they have approached them, males start the courtship by smelling the females' anal region and the marginal scutes (e.g., the divided plates of the carapace). The male then proceeds to mount the female, staying attached to the carapace by using his claws and wrapping his tail around hers. Copulation happens after the male has perpendicularly line up with the females carapace. Mating can take up to two hours and can often end with many failed attempts due to the female attempting to flee. In some cases, up to 6 males attempt to mate with a single female at the same time. In captivity, the courting process can take over 2 hours, with actual coitus taking upwards of 30 minutes. (Bels and Crama, 1994; Iverson, 1978; Niemiller, et al., 2013; Zappalorti and Iverson, 2006)

- Mating System

- polygynandrous (promiscuous)

Female loggerhead musk turtles have a longer time to mature than males. They average around 5 to 8 years while males average around 3 to 6 years. The testes of the male begin to enlarge in March and continuously enlarge until they reach their max size in August or September. The testes reduce back down to the size of juvenile males through the remaining months. This is a continuous cycle. Females ovulate from September to July and mating peaks in the morning of the months of April and May. Many males may try to mate with a single female which leads aggression between the males. The gestation period lasts for 3-7 weeks. Females annually lay 1-5 clutches containing 1-5 eggs.The eggs range from 12.7-19.5 mm in size and 1.97-6.70 g in mass. The first clutch usually occur in September and the last clutch usually occurs in May. Clutch numbers vary in between those months. The incubation period averages around 99 days. Once hatched, the turtles are immediately independent. (Cox and Marion, 1978; Ernst and Barbour, 1989; Iverson, 1978; Niemiller, et al., 2013)

- Key Reproductive Features

- iteroparous

- gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate)

- sexual

- oviparous

-

- Breeding interval

- Multiple clutches are laid From September through May.

-

- Breeding season

- September through July. Incubation lasts for an average of 99 days.

-

- Range number of offspring

- 1 to 5

-

- Average number of offspring

- 3.3

-

- Range gestation period

- 3 to 7 weeks

-

- Range time to independence

- 0 (high) minutes

-

- Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female)

- 5 to 8 years

-

- Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male)

- 3 to 6 years

After mating, males have no parental investment in loggerhead musk turtles and stripe-necked musk turtles. Once the females lay the eggs her investment ends. (Iverson, 1978)

- Parental Investment

- no parental involvement

Lifespan/Longevity

In captivity, the longest lifespan of loggerhead musk turtles is 23 years and 11 months. In the wild, the oldest recorded is 21 years, but they are believed to live longer. (Buhlmann, et al., 2008)

-

- Range lifespan

Status: captivity - 23 (high) years

- Range lifespan

-

- Average lifespan

Status: wild - 21 years

- Average lifespan

Behavior

Loggerhead musk turtles are aquatic, but they have been found to come out onto land time to time to bask on limbs and females come out to lay their eggs. They are diurnal and nocturnal species with their activity concentrated on morning hours where they have been found probing the bottom of the water for food. During the night, the turtles often switch to water that is shallow because it tends to be warmer. The water temperature usually ranges from 14-28.5 degrees Celsius. Loggerhead musk turtles that live in colder temperature waters hibernate during the winter months. They hibernate in underwater rock crevices or burrow in the mud found at the bottom of the body of water. These turtles are able to stay underwater for long periods of time by using their buccopharyngeal lining to get oxygen from the water.

Stripe-necked musk turtles spend the majority of their time probing for food. They can go through a 24 hour period of no movement. This behavior is more common during the night. Stripe-necked musk turtles hibernate during the winter months of December through January. (Buhlmann, et al., 2008; Ennen and Scott, 2008; Iverson, 1977; Niemiller, et al., 2013)

- Key Behaviors

- natatorial

- diurnal

- nocturnal

- motile

- hibernation

- social

Home Range

Stripe-necked musk turtles have a home range of 341.4 ± 90.3 m. They are not known to defend territories.

Zappalorti and Iverson (2006) reported that loggerhead musk turtles reach densities higher than any reported for turtles. In Florida, a population reached a density of 2857 individuals per hectare. (Ennen and Scott, 2013; Zappalorti and Iverson, 2006)

Communication and Perception

Aggression is rare, unless these turtles feel threatened. When both the loggerhead musk turtles and stripe-necked musk turtles are in an dangerous situation, they become aggressive and release an unpleasant odor from their musk glands. Along with the scent, the turtles bite at the attacker. They have color vision and also have shown to have a color preference for the color red. While mating, the male mounts the female followed by a series of biting, head turns, and turning. In captivity, multiple males will be aggressive towards one another in the presence of a female ready to breed. (Bels and Crama, 1994; Ernst and Barbour, 1989; Ernst and Hamilton, 1969; Hailman and Jaegar, 1971; Jackson, 1969; Zappalorti and Iverson, 2006)

Food Habits

Loggerhead musk turtles primarily feed on invertebrates and aquatic plants. As juveniles, their diet consists of millipedes, beetles, and true bugs. As loggerhead musk turtle age to adulthood, they switch to a molluscivorous diet. This diet includes mollusks such as snails and clams. They often hunt for their food at night.

The stripe-necked musk turtle primarily feeds upon insects and aquatic species such as crayfish and clams. The insects they eat include beetles, mayflies, odonates, and stoneflies. They can also be scavengers as they have been found eating dead fish. In the summer, they often eat clumps of algae that some snails are found in. Stripe-necked musk turtles are mainly carnivorous but are opportunistic. Their diet also consists of vascular plants and bits of rock. They often hunt for their food in the morning unlike the loggerhead musk turtle. (Ernst and Barbour, 1989; Folkerts, 1968; Mitchell, 1994; van Dijk, 2011)

- Primary Diet

- carnivore

- Animal Foods

- fish

- insects

- terrestrial non-insect arthropods

- mollusks

- aquatic crustaceans

- Plant Foods

- algae

Predation

Loggerhead musk turtles and stripe-necked musk turtles are known to be the prey of alligator snapping turtles (Macrochelys temminckii), cottonmouth snakes (Agkistrodon piscivorus), and American alligators (Alligator mississippiensis). Humans (Homo sapiens) are also known to be a predator. Juvenile loggerhead musk turtles are more vounreable due to their small size. Animals including raccoons (Procyon lotor) and crows (Corvus) are often found feeding upon the turtles eggs. The turtles defense against predators include biting and putting off an unpleasant odor from their musk glands. (Buhlmann, et al., 2008; Niemiller, et al., 2013)

-

- Known Predators

-

- alligator snapping turtle (Macrochelys temminckii)

- American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis)

- raccoon (Procyon lotor)

- crow (Corvus)

- human (Homo sapiens)

Ecosystem Roles

Loggerhead musk turtle parasites include a blood protozoan (Haemogregarina stepanowi), a blood fluke (Hapalorhynchus stunkardi), a nematode (Spiroxys contortus) and a lung fluke (Heronimus mollis). They also include trematodes (Eustomus chelydrae, Polystomoidella, Telochis). Adults have been caught with leeches attached, but species of leeches have not been listed. Loggerhead musk turtles don't impact their ecosystem. (Cox, et al., 1988; Ernst and Barbour, 1989; Zappalorti and Iverson, 2006)

- Blood protozoan Haemogregarina stepanowi

- Blood fluke Hapalorhynchus stunkardi

- Nematode Spiroxys contortus

- Trematode Eustomus chelydrae

- Trematode Polystomoidella

- Trematode Telorchis

- Lung fluke Heronimus mollis

- Leech

Economic Importance for Humans: Positive

Loggerhead musk turtles and stripe-necked musk turtles are sold in the pet trade. They are sold for $21.50 at reptile expositions. (Buhlmann, et al., 2008; Ceballos and Fitzgerald, 2004)

- Positive Impacts

- pet trade

Economic Importance for Humans: Negative

There are no known adverse effects of loggerhead musk turtles or stripe-necked musk turtles on humans.

Conservation Status

Loggerhead musk turtles are listed as least concern on the IUCN Red List. They are not found on US Federal list, State of Michigan list, and cites. The major threat of the loggerhead musk turtles is pollution. They are also threatened by fisherman, as these omnivorous turtles will take bait. Boats can increase the turbidity of their habitats, and boat propellers can directly harm these turtles. Conservation efforts include protection from commercial exploitation in Florida, Mississippi, and Tennessee, but lack in Alabama, Georgia, and Louisiana. Zappalorti and Iverson (2006) reported that loggerhead musk turtles reach densities higher than any reported for turtles. In Florida, a population reached a density of 2857 individuals per hectare; so in some portions of their range, these turtles are thriving. Florida allows the take of 2 individual turtles per year without a permit, and up to 50 eggs of any turtle species from the wild. Tennessee also allows the take of 2 turtles per year. Neither Florida nor Tennessee allow for these turtles to be sold. (Niemiller, et al., 2013; Zappalorti and Iverson, 2006; van Dijk, 2011)

-

- IUCN Red List

- Least Concern

-

- US Federal List

- No special status

-

- CITES

- No special status

-

- State of Michigan List

- No special status

Contributors

Miranda Dimas (author), Radford University, Alex Atwood (editor), Radford University, Layne DiBuono (editor), Radford University, Lindsey Lee (editor), Radford University, Karen Powers (editor), Radford University, Joshua Turner (editor), Radford University, Tanya Dewey (editor), University of Michigan-Ann Arbor.

Glossary

- Nearctic

-

living in the Nearctic biogeographic province, the northern part of the New World. This includes Greenland, the Canadian Arctic islands, and all of the North American as far south as the highlands of central Mexico.

- bilateral symmetry

-

having body symmetry such that the animal can be divided in one plane into two mirror-image halves. Animals with bilateral symmetry have dorsal and ventral sides, as well as anterior and posterior ends. Synapomorphy of the Bilateria.

- carnivore

-

an animal that mainly eats meat

- diurnal

-

- active during the day, 2. lasting for one day.

- ectothermic

-

animals which must use heat acquired from the environment and behavioral adaptations to regulate body temperature

- freshwater

-

mainly lives in water that is not salty.

- hibernation

-

the state that some animals enter during winter in which normal physiological processes are significantly reduced, thus lowering the animal's energy requirements. The act or condition of passing winter in a torpid or resting state, typically involving the abandonment of homoiothermy in mammals.

- insectivore

-

An animal that eats mainly insects or spiders.

- iteroparous

-

offspring are produced in more than one group (litters, clutches, etc.) and across multiple seasons (or other periods hospitable to reproduction). Iteroparous animals must, by definition, survive over multiple seasons (or periodic condition changes).

- molluscivore

-

eats mollusks, members of Phylum Mollusca

- motile

-

having the capacity to move from one place to another.

- natatorial

-

specialized for swimming

- native range

-

the area in which the animal is naturally found, the region in which it is endemic.

- nocturnal

-

active during the night

- oviparous

-

reproduction in which eggs are released by the female; development of offspring occurs outside the mother's body.

- pet trade

-

the business of buying and selling animals for people to keep in their homes as pets.

- polygynandrous

-

the kind of polygamy in which a female pairs with several males, each of which also pairs with several different females.

- scavenger

-

an animal that mainly eats dead animals

- sexual

-

reproduction that includes combining the genetic contribution of two individuals, a male and a female

- social

-

associates with others of its species; forms social groups.

- tactile

-

uses touch to communicate

- visual

-

uses sight to communicate

References

Bels, V., Y. Crama. 1994. Quantitative analysis of the courtship and mating behavior in the loggerhead musk turtle Sternotherus minor (Reptilia: Kinosternidae) with comments on courtship behavior in turtles. Copeia, 1994/3: 676-684.

Berry, J. 1975. The population effects of ecological sympatry on musk turtles in northern Florida. Copeia, 1975/4: 692-701.

Buhlmann, K., T. Tuberville, W. Gibbons. 2008. Turtles of the Southeast. Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press.

Ceballos, C., L. Fitzgerald. 2004. The trade in native and exotic turtles in Texas. Wildlife Society Bulletin, 32/3: 881-892.

Cox, W., J. Hazelrig, M. Turner, R. Angus, K. Marion. 1991. A model for growth in the musk turtle, Sternotherus minor, in a north Florida spring. Copeia, 1991/4: 954-968.

Cox, W., K. Marion. 1978. Observations on the female reproductive cycle and associated phenomena in spring-dwelling populations of Sternotherus minor in north Florida (Reptilia: Testudines). Herpetologica, 34/1: 20-33.

Cox, W., S. Wyatt, W. Wilhelm, K. Marion. 1988. Infection of the turtle, Sternotherus minor, by the lung fluke, Heronimus mollus: Incidence of infection and correlations to host life history and ecology in a Florida spring. Journal of Herpetology, 22/4: 488-490.

Ennen, J., A. Scott. 2008. Diel movement behavior of the stripe-necked musk turtle (Sternotherus minor peltifer) in middle Tennessee. The American Midland Naturalist, 160/2: 278-288.

Ennen, J., A. Scott. 2013. Home range characteristics and overwintering ecology of the stripe-necked musk turtle (Sternotherus minor pelifer) in middle Tennessee. Chelonian Conservation and Biology, 12/1: 199-203.

Ernst, C., R. Barbour. 1989. Turtles of the World. Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

Ernst, C., H. Hamilton. 1969. Color preferences of some North American turtles. Journal of Herpetology, 3/3,4: 176-180.

Ernst, C., J. Lovich. 2009. Turtles of the United States and Canada. Baltimore, Maryland: The John Hopkins University Press.

Etchberger, C., L. Ehrhart. 1987. The reproductive biology of the female loggerhead musk turtle, Sternotherus minor minor, from the southern part of its range in central Florida. Herpetologica, 43/1: 66-73.

Folkerts, G. 1968. Food habits of the stripe-necked musk turtle, Sternotherus minor peltifer Smith and Glass. Journal of Herpetology, 2/3-4: 171-173.

Gatten, R. 1984. Aerobic and anaerobic metabolism of freely-diving loggerhead musk turtles (Sternotherus minor). Herpetologica, 40/1: 1-7.

Hailman, J., R. Jaegar. 1971. On criteria for color preferences in turtles. Journal of Herpetology, 5/1,2: 83-85.

Iverson, J. 1977. Geographic variation in the musk turtle, Sternotherus minor. Copeia, 1977/3: 502-517.

Iverson, J. 1978. Reproductive cycle of female loggerhead musk turtles (Sternotherus minor minor) in Florida. Herpetologica, 34/1: 33-39.

Jackson, C. 1969. Agonistic behavior in Sternotherus minor minor Agassiz. Herpetologica, 25/1: 53-54.

Mitchell, J. 1994. The Reptiles of Virginia. Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Neill, W. 1948. Use of scent glands by prenatal Sternotherus minor. Herpetologica, 4/4: 148.

Niemiller, M., G. Reynolds, B. Miller. 2013. The Reptiles of Tennessee. Knoxville, Tennessee: The University of Tennessee Press.

Ontorato, D. 1996. The growth rate and age distribution of Sternotherus minor at Rainbow Run, Florida. Journal of Herpetology, 30/3: 301-306.

Pfaller, J., P. Gignac, G. Erickson. 2011. Ontogenetic changes in jaw-muscle architecture facilitate durophagy in the turtle Sternotherus minor. Journal of Experimental Biology, 214/10: 1655-1667.

Seidel, M., S. Reynolds, R. Lucchino. 1981. Phylogenetic relationships among musk turtles (genus Sternotherus) and genic variation in Sternotherus odoratus. Herpetologica, 37/3: 161-165.

Steen, D., M. Baragona, C. McClure, K. Jones, L. Smith. 2012. Demography of a small population of loggerhead musk turtles (Sternotherus minor) in the panhandle of Florida. Florida Field Naturalist, 40/2: 47-55.

Zappalorti, R., J. Iverson. 2006. Sternotherus minor – loggerhead musk turtle. Pp. 197-206 in P Meylan, ed. Biology and Conservation of Florida Turtles, Vol. Chelonian Research Monographs 3. Lunenburg, Massachusetts: Chelonian Research Foundation.

van Dijk, P. 2011. "Sternotherus minor (errata version published in 2016)." (On-line). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2011: e.T170493A97384102.. Accessed February 09, 2018 at http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-1.RLTS.T170493A6781671.en.3/0.