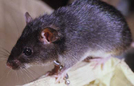

Rattus exulansPolynesian rat

Geographic Range

Polynesian rats (Rattus exulans) have an extensive distribution from Southeast Asia and New Guinea through the Pacific. They spread to several thousands islands in the western and central Pacific Ocean through the colonizing efforts of the Polynesian people. The rats were carried along on the large sea-going canoes with pigs, dogs and jungle cocks. (Dwyer, 1978; Masaharu, et al., 2001; Tobin, 1994; Walton, et al., 1980)

- Biogeographic Regions

- palearctic

- oriental

- australian

- oceanic islands

Habitat

Rattus exulans can live in a variety of habitats including grassland, scrub and forests, provided that it has adequate food supplies and shelter. It is not a good swimmer, but is able to climb trees for food. Other habitats include the those created by humans, such as houses, granaries, and cultivated lands. These rats usually lives below 1,000 m in elevation, where there is good ground cover and well-drained soil. (Masaharu, et al., 2001; Russell, 2002; Tobin, 1994; Williams, 1973)

- Habitat Regions

- temperate

- tropical

- terrestrial

- Terrestrial Biomes

- savanna or grassland

- forest

- scrub forest

- Other Habitat Features

- urban

- suburban

- agricultural

-

- Range elevation

- 1,000 (high) m

- ft

Physical Description

Rattus exulans has a slender body, pointed snout, large ears and relatively delicate feet. Its back is a ruddy-brown color, with a whitish belly. Mature Polynesian rats are 11.5 to 15.0 cm long from the tip of the nose to the base of the tail. Average weoght is between 40 and 80 g. The tail has fine, prominent, scaly rings, and is about the same length as the head and body combined. Female R. exulans have eight nipples. The skull size has been shown to vary with latitudem with those from cooler climates being larger than those living in warmer climates. A useful feature to distinguish this rat from other species is a dark outer edge on the upper side of the hind foot near the ankle while the rest of the foot is pale. (Russell, 2002; Tobin, 1994)

- Other Physical Features

- endothermic

- homoiothermic

- bilateral symmetry

-

- Range mass

- 40 to 80 g

- 1.41 to 2.82 oz

-

- Range length

- 11.5 to 15 cm

- 4.53 to 5.91 in

Reproduction

Polynesian rats breed throughout the year with peak breeding occuring in summer and early fall. (Tobin, 1994)

Reproduction varies among geographic areas and is influenced by the availability of food, weather, and other factors. Females have an average of 4 litters per year with and average of 4 young per litter. In New Zealand, gestation is 19 to 21 days and weaning occurs at 2 to 4 weeks. Sexual maturity is reached by 8 to 12 months, though adult size can be achieved during the same season as birth. (Russell, 2002; Tobin, 1994; Williams, 1973)

- Key Reproductive Features

- iteroparous

- seasonal breeding

- year-round breeding

- gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate)

- sexual

- fertilization

- viviparous

-

- Breeding interval

- These rats can breed up to four times per year, depending on weather, food availability and climate.

-

- Range number of offspring

- 1 to 4

-

- Average number of offspring

- 4

-

- Range gestation period

- 19 to 21 days

-

- Range weaning age

- 2 to 4 weeks

-

- Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female)

- 8 to 12 months

-

- Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male)

- 8 to 12 months

Not much is known about the parental care of Polynesian rats. They are placental mammals that have dependent young. Young are probably altricial, as is common in the genus. While they develop, they probably live in some sort of nest, where they are nurse, groomed, and protected by their mother. (Russell, 2002)

- Parental Investment

- no parental involvement

- altricial

-

pre-fertilization

-

protecting

- female

-

protecting

-

pre-hatching/birth

-

provisioning

- female

-

protecting

- female

-

provisioning

-

pre-weaning/fledging

-

provisioning

- female

-

protecting

- female

-

provisioning

-

pre-independence

-

protecting

- female

-

protecting

Lifespan/Longevity

The lifespan of Polynesian rats is up to one year in the wild. In capitivity this species can live up to 15 months. (Russell, 2002; Tobin, 1994; Williams, 1973)

-

- Typical lifespan

Status: wild - 1 (high) years

- Typical lifespan

-

- Typical lifespan

Status: captivity - 12 to 15 months

- Typical lifespan

Behavior

Polynesian rats are an opportunistic species. In the absence of other rodents they exploit a variety of habitats, ranging from rainforest to grasslands, are able to tolerate different climatic regimes, and are able to persist for long periods at low densities. (Dwyer, 1978)

During the sugar cane harvest, the rats living in the fields either die or migrate to surrounding areas. During the second half of the crop cycle they will rebuild their populations. (Tobin, 1994)

Home Range

Polynesian rats are relitively sedentary and nocturnal. Males travel further than females, but the home range for both sexes decreases as the sugarcane matures. (Tobin, 1994)

Communication and Perception

Information on communication in Polynesian rats is not available. However, as mammals, it is likely that they use some visual signals in communication. Tactile communication is undoubtedly present, especially between mates and between a mother and her offspring. Scent cues are probably used, also. (Tobin, 1994)

Food Habits

Polynesian rats eat a variety of foods, including broad leaf plants, grasses, seeds, fruits, and animal matter. They prefer fleshy fruits such as guava, passion fruit, thimbleberry, and their favorite sugar cane. Rats that live on the edges of sugar cane fields consume sugar cane as 70% of their diet. To acquire the other additional proteins it will eat earthworms, spiders, cicadas, insects, and eggs of ground nesting worms. (Dwyer, 1978; Russell, 2002; Tobin, 1994; Williams, 1973)

- Primary Diet

- omnivore

- Animal Foods

- eggs

- insects

- terrestrial non-insect arthropods

- terrestrial worms

- Plant Foods

- leaves

- seeds, grains, and nuts

- fruit

Predation

The infestation of Polynesian rats has destroyed the sugar cane fields, especially in Hawaii. To protect the fields in Hawaii, Indian mongooses (Herpestes auropunctatus) were introduced from the West Indies to help control the rats. Barn owls and dogs have also been used to get rid of Polynesian rats. (Russell, 2002; Tobin, 1994; Williams, 1973)

-

- Known Predators

-

- Indian mongooses (Herpestes auropunctatus)

- barn owls (Tyto alba)

Ecosystem Roles

As a prey species, these animals undoubtedly affect predator populations. In their foraging, they affect plant communities, as well as populations of small invertebrates upon which they prey.

Economic Importance for Humans: Positive

Polynesian rats have no positive economic importance to humans. (Tobin, 1994)

Economic Importance for Humans: Negative

Polynesian rats are a major agricultural pest throughout Southeast Asia and the Pacific region. Crops damaged by this species include root crops, cacao, pineapple, coconut, sugarcane, corn, and rice. (Russell, 2002)

- Negative Impacts

- crop pest

Conservation Status

Rats are an exotic species in Hawaii and are not protected by law. The rats can be controlled by any method consistent with state and federal law regulations. Mongoose and monitor lizards were introduced to the Pacific islands to attempt to control R. exulans. (Russell, 2002; Tobin, 1994)

-

- IUCN Red List

-

Least Concern

More information

-

- IUCN Red List

-

Least Concern

More information

-

- US Federal List

- No special status

-

- CITES

- No special status

Contributors

Nancy Shefferly (editor), Animal Diversity Web.

Donna Warren (author), University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point, Chris Yahnke (editor), University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point.

Glossary

- Australian

-

Living in Australia, New Zealand, Tasmania, New Guinea and associated islands.

- Palearctic

-

living in the northern part of the Old World. In otherwords, Europe and Asia and northern Africa.

- acoustic

-

uses sound to communicate

- agricultural

-

living in landscapes dominated by human agriculture.

- altricial

-

young are born in a relatively underdeveloped state; they are unable to feed or care for themselves or locomote independently for a period of time after birth/hatching. In birds, naked and helpless after hatching.

- bilateral symmetry

-

having body symmetry such that the animal can be divided in one plane into two mirror-image halves. Animals with bilateral symmetry have dorsal and ventral sides, as well as anterior and posterior ends. Synapomorphy of the Bilateria.

- chemical

-

uses smells or other chemicals to communicate

- endothermic

-

animals that use metabolically generated heat to regulate body temperature independently of ambient temperature. Endothermy is a synapomorphy of the Mammalia, although it may have arisen in a (now extinct) synapsid ancestor; the fossil record does not distinguish these possibilities. Convergent in birds.

- fertilization

-

union of egg and spermatozoan

- forest

-

forest biomes are dominated by trees, otherwise forest biomes can vary widely in amount of precipitation and seasonality.

- introduced

-

referring to animal species that have been transported to and established populations in regions outside of their natural range, usually through human action.

- iteroparous

-

offspring are produced in more than one group (litters, clutches, etc.) and across multiple seasons (or other periods hospitable to reproduction). Iteroparous animals must, by definition, survive over multiple seasons (or periodic condition changes).

- motile

-

having the capacity to move from one place to another.

- native range

-

the area in which the animal is naturally found, the region in which it is endemic.

- oceanic islands

-

islands that are not part of continental shelf areas, they are not, and have never been, connected to a continental land mass, most typically these are volcanic islands.

- omnivore

-

an animal that mainly eats all kinds of things, including plants and animals

- oriental

-

found in the oriental region of the world. In other words, India and southeast Asia.

- scrub forest

-

scrub forests develop in areas that experience dry seasons.

- seasonal breeding

-

breeding is confined to a particular season

- sedentary

-

remains in the same area

- sexual

-

reproduction that includes combining the genetic contribution of two individuals, a male and a female

- suburban

-

living in residential areas on the outskirts of large cities or towns.

- tactile

-

uses touch to communicate

- temperate

-

that region of the Earth between 23.5 degrees North and 60 degrees North (between the Tropic of Cancer and the Arctic Circle) and between 23.5 degrees South and 60 degrees South (between the Tropic of Capricorn and the Antarctic Circle).

- terrestrial

-

Living on the ground.

- tropical

-

the region of the earth that surrounds the equator, from 23.5 degrees north to 23.5 degrees south.

- tropical savanna and grassland

-

A terrestrial biome. Savannas are grasslands with scattered individual trees that do not form a closed canopy. Extensive savannas are found in parts of subtropical and tropical Africa and South America, and in Australia.

- savanna

-

A grassland with scattered trees or scattered clumps of trees, a type of community intermediate between grassland and forest. See also Tropical savanna and grassland biome.

- temperate grassland

-

A terrestrial biome found in temperate latitudes (>23.5° N or S latitude). Vegetation is made up mostly of grasses, the height and species diversity of which depend largely on the amount of moisture available. Fire and grazing are important in the long-term maintenance of grasslands.

- urban

-

living in cities and large towns, landscapes dominated by human structures and activity.

- visual

-

uses sight to communicate

- viviparous

-

reproduction in which fertilization and development take place within the female body and the developing embryo derives nourishment from the female.

- year-round breeding

-

breeding takes place throughout the year

References

Dwyer, P. 1978. A study of Rattus exulans in the New Guinea highlands. Australian Wildlife Research, 5/2: 221-248.

Masaharu, M., L. Kau-Hung, H. Masashi, L. Liang-Kong. 2001. New records of Polynesial Rat Rattus exulans (Mammalia:Rodentia) from Taiwan and the Ryukyus. Zoological Studies, 40/4: 299-304.

Russell, J. 2002. "Rattus exulans" (On-line). Global Invasive Species Database. Accessed October 24, 2002 at http://www.issg.org/database/species/search.asp?sts=sss&st=sss&fr=1&sn=Polynesian+rat&rn=&hci=-1&ei=-1&x=33&y=11.

Tobin, M. 1994. Polynesian Rats. Prevention and Control of Wildlife Damage: 121-124.

Walton, D., J. Brooks, K. Thinn, U. Tun. 1980. Reproduction in Rattus exulans in Rangoon, Berma. Mammalia, 44/3: 349-360.

Williams, M. 1973. The Ecology of Rattus exulans (Peale) Reviewed. Pacific Science, 27/2: 120-127.